A brief history of creativity (and power)

Creativity was once reserved for the gods. Now it seems to be the domain of the powerful. How did we get here?

This essay was originally published in Lens

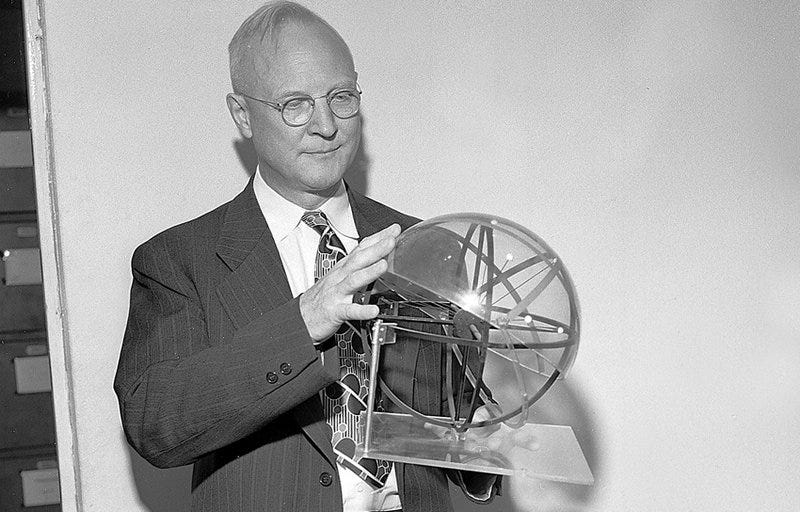

In September 1950, American psychologist J.P. Guilford delivered an address at Pennsylvania State College, warning of an impending industrial revolution that would far outshine the transformations of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. “The first one made man’s muscles relatively useless,” he said. “The second one is expected to make man’s brain also relatively useless.” Guilford’s keynote lecture unilaterally established an urgency for continued creativity research within the scientific community, making evident the social and economic rewards of unlocking its mysteries.

The severity of his words seems befitting of the AI-aided labor crossroads at which we find ourselves today. Advances in image and text generation seem like they will inevitably supplant our current state of creative work. When I hear artists and AI evangelists argue about whether people who generate text using ChatGPT or images using Midjourney are truly creative, I wonder about the question behind the question. What is at stake when we ask whether something is creative? The word "creativity" can at times feel almost inevitable, its cultural connotations inseparable from art and artists. But history tells a different story.

Creativity may feel like the beginning of everything, but in the beginning there was no creativity. In 1950, when Guilford delivered his address, creativity as a field of research was virtually nonexistent. In fact, the word “creativity” itself was a recent invention, having only been inducted into standard English dictionaries after World War II.

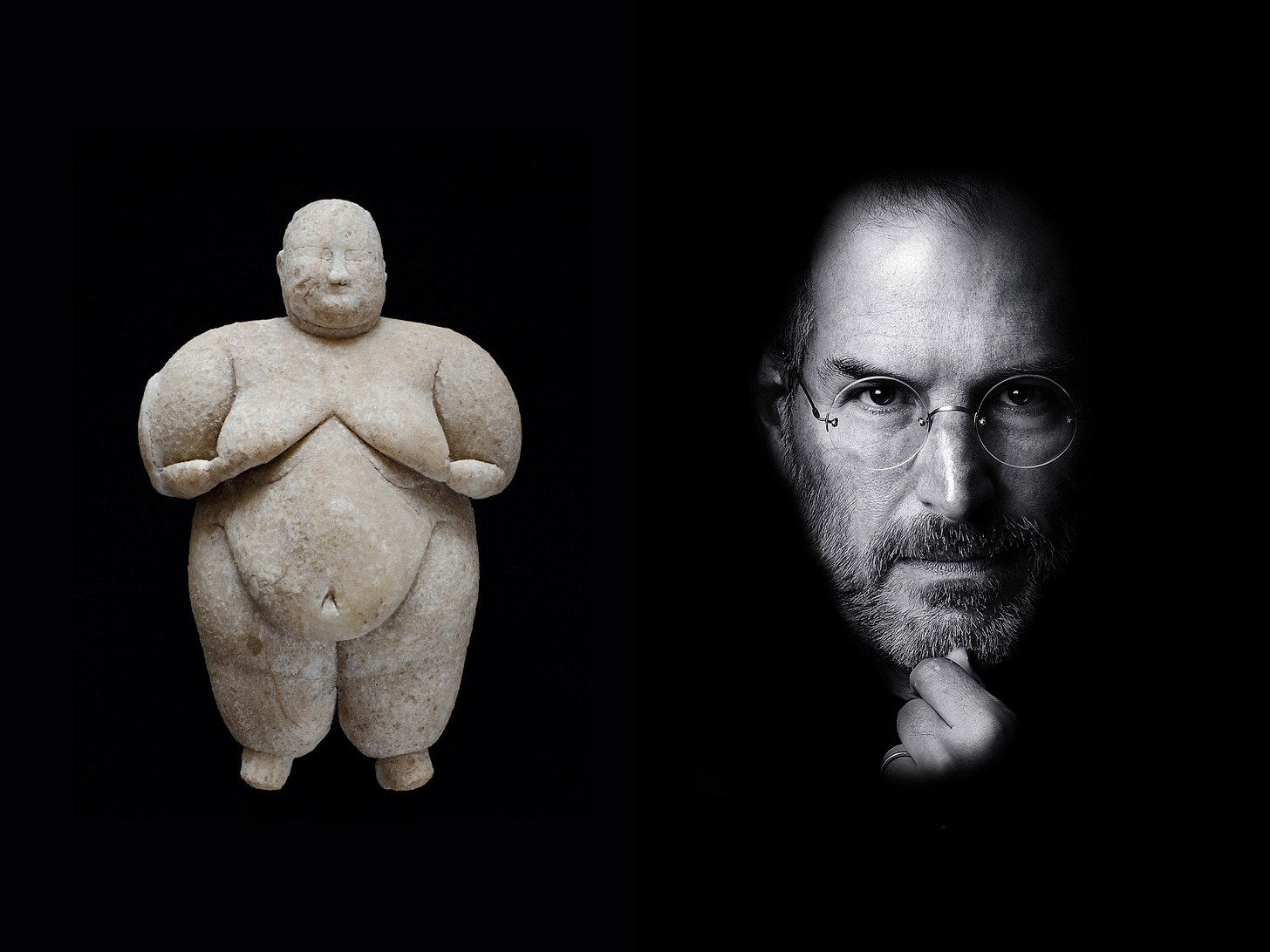

Pre-archaic cultures not only lacked the language to describe creative acts, but their sociological values were often at odds with the pursuit of originality. In order to access what might be the seeds of modern creativity, we must enter the realm of the gods. Early Mesopotamian theology was ripe with all-powerful female goddesses like Ishtar in Babylonia, who expressed their power through their ability to give birth. Pre-creativity was expressed primarily through procreativity.

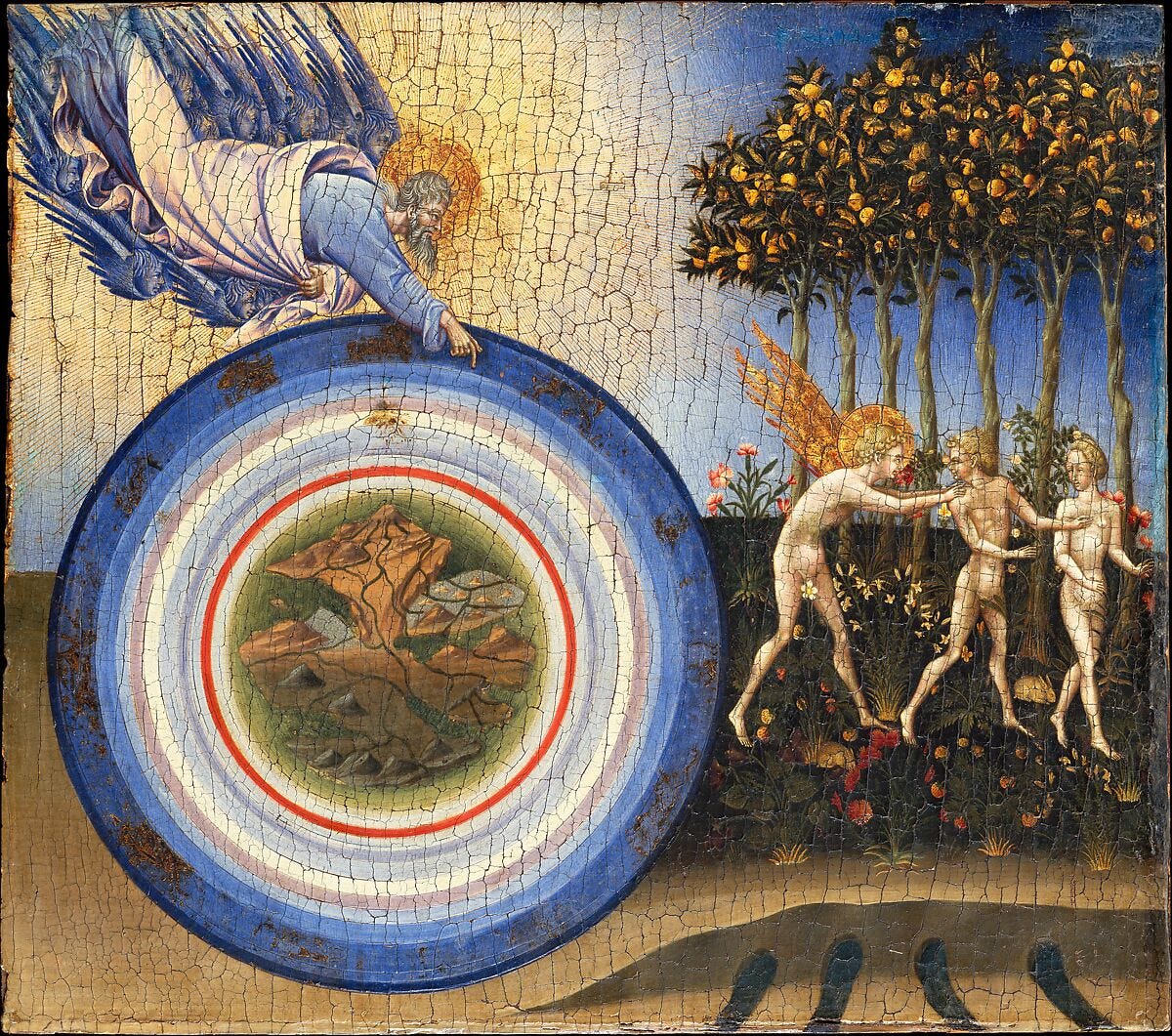

How we get from a goddess creating through birth to the (typically male) creative entrepreneurs on the covers of magazines is mainly a story about power. Slowly but surely, male gods climbed the creative ladder, first assisting goddesses in procreation, but eventually overtaking them, as people sought out forms of religious worship that more closely reflected the patriarchal hierarchies of the real world. The invention of writing brought with it an obsession with the power of the kind of immortality that comes from naming something and recording it into history. This was useful to the ancients, as it allowed them to redirect creation from birthing (by women) to breathing and speaking (by men).

The Old Testament story of creation grafted this power from god to man: Adam not only named the animals, but Eve was both born of his ribs and named by his mouth, establishing his dominance over her. Historian Gerda Lerner says that this marks a "counterfactual account of the origin of human life" in which man is literally the woman's mother.

Aristotle took this counterfactual account one step further by elevating it to the level of science, claiming that semen is the primary creator of life, and that the woman's body is only material for the semen to work with.

Pay attention to this move, as it will repeat itself in the modern-day manifestations of creativity. Science may be the pursuit of truth, but scientific language is adept at dressing up insidious ideologies as fundamental truths.

With few exceptions, the ancient Greeks did not seem to value newness; on the contrary, they idealized the precise observation and replication of the old. Even the arts, which today seem conceptually inseparable from the pursuit of novelty, were for the moment expressed through rules (the Greek word for art, techne, literally means “the making of things, according to rules”). To the question of whether the painter creates, Plato responded: “Certainly not, he merely imitates.”

It is not until Christian theology that gods began creating from nothing (ex nihilo), rather from existing materials: "Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made" (John 1:3). During the Renaissance, this doctrine of ex nihilo was applied to people—specifically, artists.

However, thinkers hesitated to use "creative," a word still associated with godly creation. The Italian philosopher and priest Marsilio Ficino described artists like Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo as "employ[ing] shapes that do not exist in nature," or "invent[ing] what is not."

It was a seventeenth century Latin poet, Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski, who at last broke the seal and used the word that would forever connect the inventiveness of art explicitly with divinity, saying that the poet "creates anew" (de novo creat) in the manner of god.

The appropriation of creativity from divinity meant that art and artists were thought of as eluding understanding. In the Romantic era, this association gave male artists free reign to be creative, but also served as justification for any lapse in the genius's morality. As long as he was being creative, man could be homosexual, licentious, or otherwise "unethical." Fast-forward to the induction of the word "creativity" into French and Italian dictionaries in the early twentieth century, marking the linguistic uncoupling of human artistry from divine creation. Fast-forward again to Guilford's 1950 address, marking a surge in scientific interest in creativity.

As we learned, a vague gesture toward science can further entrench ideologies, making them invisible. The scholarship that followed to some extent did to creativity what Aristotle did to creation. This is evidenced in attempts to define creativity, which often devolved into tautology. Guilford defined creativity as “the abilities that are most characteristic of creative people." The widely popular sociocultural approach defined creativity as "the generation of a product that is judged to be novel and also to be appropriate, useful, or valuable by a suitably knowledgeable social group." The question that naturally follows is: what comprises a "suitably knowledgeable social group?"

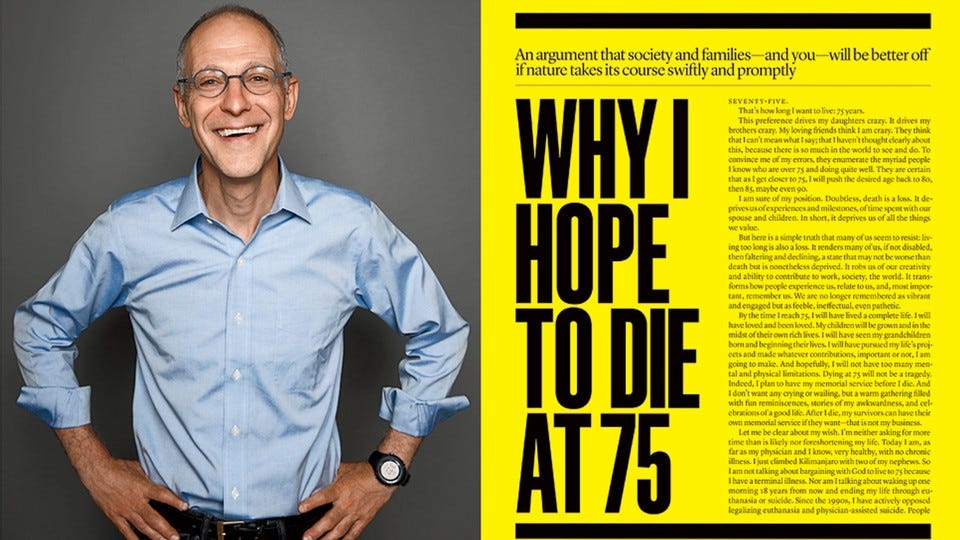

Creativity researcher Dean Keith Simonton went so far as to describe creative people as those "whose contributions are acknowledged by contemporary and future generations." The tendency of history to undervalue the contributions of certain groups of people is well documented. Wikipedia, to give one example, estimated that as of 2017, only 17% of its biographies were about women. These definitions have ripple effects: in the Atlantic, bioethicist Zeke Emanuel cited Simonton's research on creative output in old age in order to argue that U.S. healthcare policy should not be concerned with extending people's lives past a certain age (a twisted but appropriate irony for a word descending from procreativity). Emanuel served as health policy advisor during the Obama administration.

Once again, the people who were already assumed to be creative were solidified in their positions of power, the assumption hidden behind science.

What should we make of this history? When we look at the evolution of creativity, one story that can be told is that it was a concept designed to extricate divine procreative power from women and give it to men.

There are other stories to tell as well. In the twentieth century, creativity became enmeshed with capitalistic productivity, and its study was largely centered around the fields of consumer psychology, organizational management, and product marketing. In other words, the thing being created by creativity is value.

The relationship between creativity and power becomes so strong that it allows for two seemingly contradictory things to occur in parallel: when exercised by the managerial class, it is used to grant capital (think: the deification of the startup founder), and when exercised by the working class, it is used to deny capital (think: the frivolousness ascribed to arts education). Relatedly, the ultimate manifestation of this relationship is the creative logic of social media, wherein users create the content and platforms reap the monetary rewards.

An exercise: whenever you hear a person or activity described as "creative," silently replace the word with "godly." Then ask yourself:

Who is granting this power?

Who is being granted this power? Who is it being withheld from?

Who profits from this allocation of power? Who is harmed by it?

I am not suggesting that creativity is universally bad. I am suggesting that novelty only scratches the surface of what this word can do. When I look at the history of creativity, I see a succession of forgotten, undervalued, silenced, and ignored meanings waiting to be unlocked. We will explore these meanings in part 2 of this series.