Turning TikTok against itself

What happens when you train Tiktok to show you videos you'll hate

It may be unpopular to say, but I would sell my data-atomized soul to TikTok in a heartbeat. I find the idea of an algorithm knowing me that well kind of alluring—like a personality test, or living in a world in which I actually relate to astrology memes, or falling in love. I wonder, what would I learn about myself? What interests and aesthetics (bricklaying? Desertwave?) lay dormant in my subconscious, ready to be unlocked by VC-funded neural networks?

So what prevented me from downloading TikTok was not paranoia but pragmatism, a belief in the power of the Algorithm to pull me into a blissful black hole, never to return again.

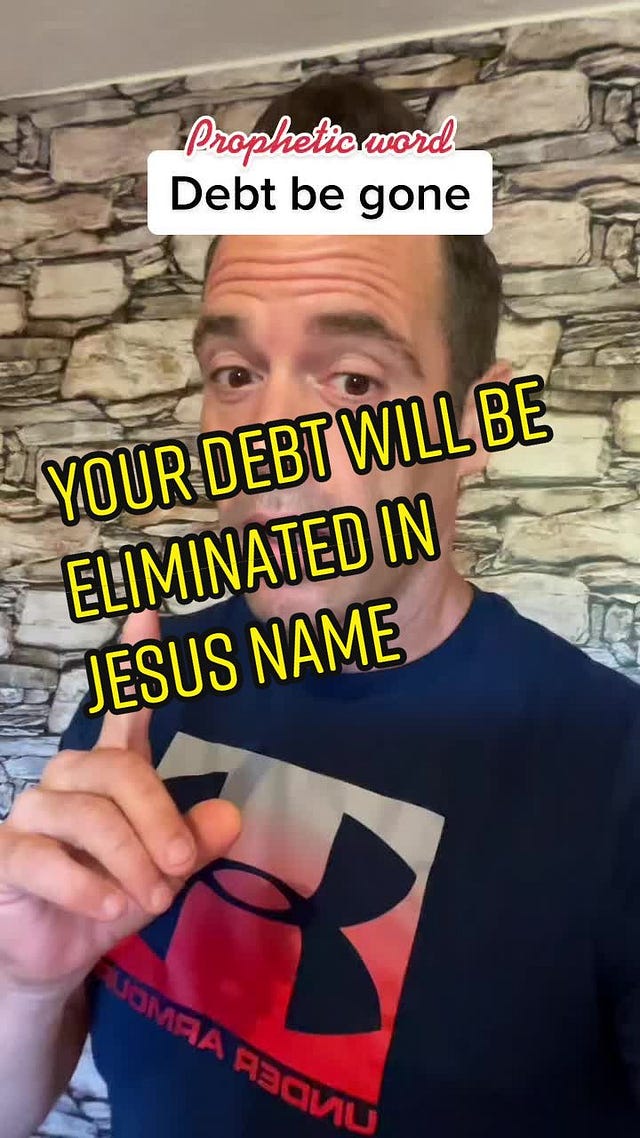

But the idea that I could be seen in some way kept drawing me back. So by way of compromise, I created a kind of bizarro TikTok account—call it an IckTok— in which I train the recommendation engine to feed me videos I won't like. The rules are simple: as soon as a video grabs my attention, I swipe; if I find a video boring or repulsive, I stick around. Fast forward a few days, and voila, an infinite feed of my worst nightmares, an anti-addictive, perverse reflection of my id.

Plenty of ink has been spilled about whether echo chambers are good or bad. What I will say is that it’s surreal to cross a chasm just by diverting your attention, like sitting in a self-driving car.

It’s an experiment I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy. But at the same time, it gave me an adrenaline rush. I was tricking the devil, and in so doing I felt I could see Him from a radically different angle.

Here’s what I expected to see: fishing, pro wrestling, hunting, grilling, the kind of content that assumes all cars don’t look exactly the same to me. I expected to be bored, and I thought there might be an almost meditative quality to the ennui, like listening to a conversation in a foreign language.

But as it turns out, IckTok was way less likely to show me content that made me numb; instead, my feed became an endless barrage of videos that repulsed me. Maybe it’s because other people’s obsessions can be deeply interesting if you look at them closely enough (which, according to the logic of my experiment, would compel me to swipe past them). Or maybe because TikTok has decided that attention born out of tantalization is more profitable than that born out of enrichment. In place of videos of sports, I saw a dermatologist reacting like a sportscaster to a close up of pimples being popped. In place of window caulking, I saw Jordan Peterson.

I wondered, is there an inverse to the Law of Repulsion on right-side-up TikTok as well? Does the opposite of a pimple popping video (which for someone else may in fact be a pimple popping video) have a stronger gravitational pull than the opposite of a window caulking video?

There is something unnerving about the possibility that our inquisitive instincts are being supplanted, like a tooth fairy came in the dead of night and replaced our teeth with 32 tongues, all of our future meals to be administered in slurry form.

But I also found myself holding a deep sense of shame. There was an entire week in which the algorithm continuously fed me a very particular genre of reaction video: the audio is of someone talking about [presumably, silenced] men’s point of view.

Men are very mistreated in this country. Think about it: they’re taught to be ashamed of their masculine nature. If they call too much, they’re needy; if they don’t call enough, they’re an asshole. If they dare open the door for a woman or offer to lift a heavy box, they’re sexist. If they compliment a woman, they’re a pig; if they don’t compliment a woman, then they’re judgmental…

Meanwhile, an attractive woman stares at the camera, tears swelling in her makeup-saturated eyes. Patriarchal empathy porn.

I feel the woman looking at me, talking to me. I want to tell her that she doesn’t need to feel sorry for me. But of course she can’t hear me, she doesn’t care. So what is behind my insecurity?

We're so used to performing our attention in a way that trains platforms to give us content that fits the mold of how we see ourselves. We watch meditatively as these versions of us are sold off, greet them as old friends when we encounter them on other platforms, and reincorporate them into our identities in an endless, anxious loop. Behind the question of who am I lies an even deeper fear: is the algorithm judging me?

This piece was originally published in Dirt.

Just another number